We are entering a new age, and I think we all feel this to be so.

What this new age will be like, I cannot even imagine, still less predict with anything approaching the assuredness of prophets or madmen. But this I believe, and I suspect that you believe it as well: this is not to be an age that one can sit out, and hope for the best.

All of us are called upon to do our part, whatever that may be. I can scarcely fathom what my part is meant to be; I suppose that is why I have chosen to write these essays in the first place. My inchoate idea for this project is as a kind of catharsis, a sort of working through a spiritual malaise, in the probably forlorn hope that I’ll figure it all out somewhere along the way.

So history is being made—what of it? That is the nature of history, isn’t it? It is always unfolding before our very eyes; but this time it feels different, as though it is accelerating, as though the pace and tempo of change is quickening in ways that are both frightening and exhilarating.

It is—as the great French metaphysicist René Guénon assured us would happen in these latter days—as if the very experience of time itself were speeding up in anticipation of history’s final dénouement.

And that makes it all feel very personal, as if history has come down to our level, and that we each have a role to play. It is no longer the unique preserve of great empires, indomitable personalities, and impersonal forces. Even the least of us has a place in the great drama, and it is up to us to discover that place and perform our part as best we can.

My background is a humble one, and there is precious little I have to offer the world. Still, during a lifetime of study, of research, of timid but persistent exploration in some of the less-trodden and more thoroughly shunned avenues of knowledge, I have collected a number of curious ideas and notions, like some kind of intellectual “rag-and-bone man.”

I rather enjoy that image; it seems somehow to suit my personality.

As I said, we all feel that things have changed. The zeitgeist, the “time-spirit” that haunts our particular neck of the woods in the great sweep of ages, appears to be an outré one; it delights in upending our cherished certitudes and overturning the comfortable scientistic platitudes we’ve been reassuring ourselves with for a great long while now. After all, this should come as no great surprise, and it is only that we have forgotten so much—deliberately or otherwise—in the dense crassness and stupidity of our aberrant modern civilization that we should have reached this impasse in the first place.

I am, as you have probably already gathered, an adherent to the Traditionalist school, if that fascinating intellectual current can be so called; it is really no “school” at all, but rather a return to a way of thinking that characterized most of mankind, before the onset of what we are pleased to call “modern” civilization. That is to say, it is a healthy and normal way of thinking; it isn’t poisoned by the disease of modernity, as so much of what passes for “thinking” inevitably is these days.

Anyhow, the Traditionalists have a special way of thinking about time. They say that it moves in vast cycles, and they point to the great traditions by way of evidence. The Greeks, as anyone who remembers their Hesiod can attest, had their ages of Gold, Silver, Bronze and Iron;1 the Hindus, the Persians, the Hopis, and many others had something very similar.

And all of these traditions concur that our age is the Age of Iron—the Kali-Yuga in the Hindu tradition, the final age, ere the cycle begins anew. It is an age of aberrancy, of spiritual apostasy, of high strangeness, of degeneracy and decline and general moral and intellectual inanition. It is an age when man has turned his back upon That Which is Above, and opened his heart and his soul to That Which is Below.

In his great masterpiece, La Règne de la Quantité et les Signes des Temps, René Guénon speaks at length of the progressive “solidification” of the world, by which he means the incremental descent of humanity from the spiritual pole to the material. This process has occurred throughout the cycle, reaching its extreme nadir in our own age, the Kali-Yuga. Ours is an age of scientism and relentless, corrosive materialism, and Guénon argues that this has created a kind of shell, a cyst of sorts, that constitutes an irreparable rupture between us and the superior world.

But the same cannot be said for the other direction. Guénon maintains that not only does the sejunction between our modern understanding of the world and the actual state of things grow more glaringly obvious with each day, but that an increasing number of cracks in our materialist “shell” admit the entry of unsuspected entities and influences from the inferior world.

“However far the ‘solidification’ of the sensible world may have gone, it can never be carried so far as to turn the world into a ‘closed system’ such as is imagined by the materialists…in actual fact, as we have seen, the point corresponding to a maximum of ‘solidification’ has already been passed, and the impression that the world is a ‘closed system’ can only from now onward become more and more illusory and inadequate to the reality. ‘Fissures’ have been mentioned previously as being the paths whereby certain destructive forces are already entering, and must continue to enter ever more freely; according to traditional symbolism these ‘fissures’ occur in the ‘Great Wall’ that surrounds the world and protects it from the intrusion of malefic influences coming from the inferior subtle domain.”2

I believe that the Sufi savant has alighted upon the very nature of our age; the fissures in the Great Wall are growing larger, day by day, and “things” are once more gaining ingress to our world after a long hiatus. A lifetime spent in curious inquiries and rather unsavory pursuits has privileged me to be more aware of these matters than most, perhaps, and so I have decided to impart some of what I have learned to a world that nowadays may be in a somewhat more receptive frame of mind.

Another Traditionalist, Martin Lings, explained that as we near the end of the cycle, as the Eschaton approaches, the spiritual dilapidation of mankind is to some extent compensated for by the greater availability of sacred and esoteric knowledge, which are indeed as pearls cast before swine, but intended for those with eyes to see and ears to hear.

“[T]hanks to what is most positive in this day of conflicting opposites, the highest and deepest truths have become correspondingly more accessible, as if forced to unveil themselves by cyclic necessity, the macrocosm’s need to fulfil its aspect of terminal wisdom.”3

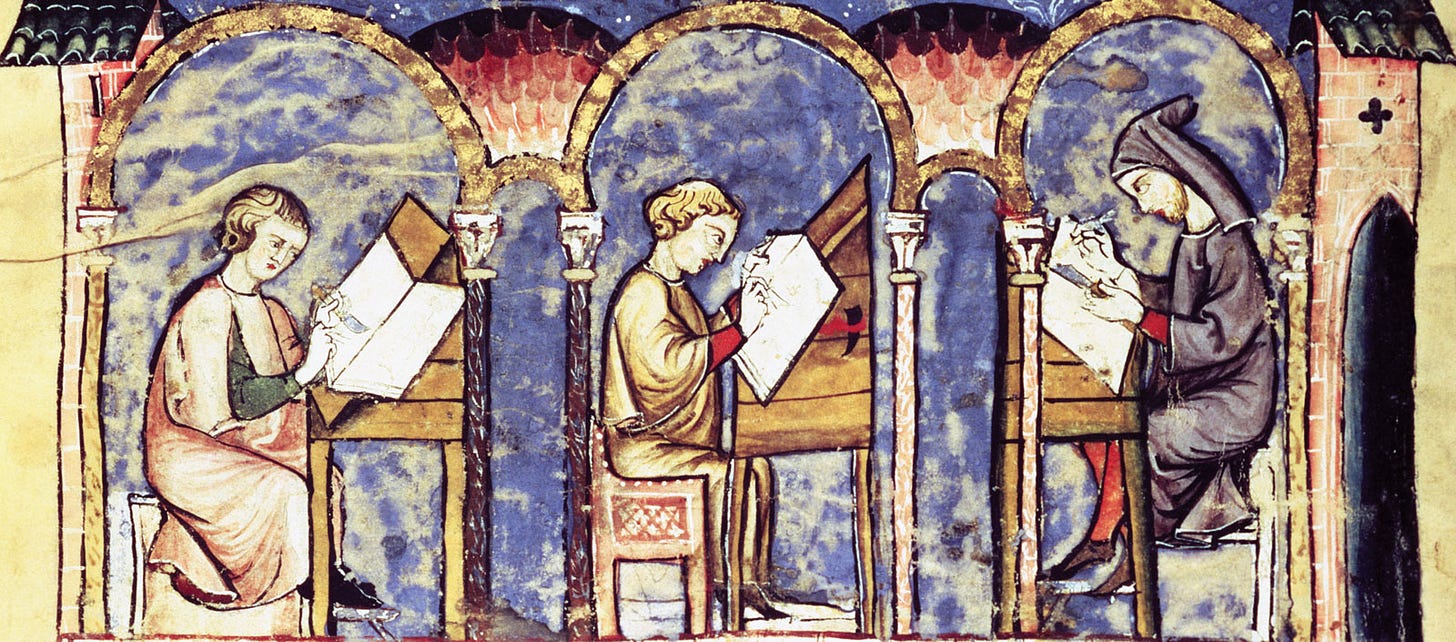

And Lings further observes: “[a] general sense of the need to place everything on record—a sense that seems to be more collective than individual—has brought forth not only a spate of encyclopaedias but also a wealth of translations.”4

This is where I find myself today, attempting in my little way to contribute what modicum of recondite and perhaps forbidden wisdom I have stored up in a misspent life. It is why I have chosen “The Cyclopedist” as the title for this project. A cyclopedist is not an encyclopedist; the two are very different creatures, and let any who confuse the two be eternally abominated.

In the terminal age in which we find ourselves, in the Kali-Yuga, there is an endless proliferation of encyclopedists; from the multiplying political tripe to the metastasizing drivel of countless inferior scribblers, there is no shortage of Wikipedias and Google algorithms to sate the vulgar and the profane.

To hell with that.

My aim here is to compile a Cyclopedia, a compendium of arcane wisdom and musings, of esoteric and forgotten knowledge, as my small and entirely inadequate contribution to what Lings believes is an unconscious and collective effusion of sacred and perhaps even forbidden gnosis, an inevitable byproduct of the natural dénouement of our cycle.

Welcome to The Cyclopedist.

Cf. Ovid’s Metamorphoses (I:128-131):

“protinus inrupit venae peioris in aevum

omne nefas, fugere pudor verumque fidesque;

in quorum subiere locum fraudesque dolique

insidiaeque et vis et amor sceleratus habendi.”

(“At once there appeared every evil in this age of baser metal; shame, truth, and honor fled, and in their place stole fraud, deceit, and artifice, violence and love of perfidy.”)

René Guénon, La Règne de la Quantité et les Signes des Temps (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1945), pg. 172. [The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times (Hillsdale NY: Sophia Perennis, 2001).]

Martin Lings, The Eleventh Hour: The Spiritual Crisis of the Modern World in the Light of Tradition and Prophecy (Cambridge: Archetype, 2002), pg. 59. This short book, from which I drew the title of this essay, is an excellent primer on Traditionalist thought, and is highly recommended.

Ibid., pg. 69.